Swift Asynchronous Programming and Error Handling Using Google/Promises

Background

I happened to find out about google/promises around January or February this year. I saw the introduction and a few lines of the sample code, and thought, ‘I need to try using it’. What kind of framework is well-introduced in GitHub, so I won’t explain it in much detail here, but if I summarize it in one line, I can say it can solve the nested closures problem caused by the iOs’s characteristics of processing the results of the asynchronous tasks using a completion handler. On top of that, the error handling becomes clean as a bonus.

The reason why I thought I should use Promises as soon I found out about it was because I thought this library would help me achieve the things that I wanted to try with my codes before.

- Chaining of functions without side effects

- Error handling that is meaningful to the user

- Minimal tuning(dependency)

I thought these small goals would help me reach the final goal of creating code that’s easy to read and giving the users a better experience.

Chaining functions w/o side effects

After the announcement at the 2016 D2 iOS Open Seminar, I got to know the leader of the team that developed Papago and Whale Browser and worked with that team for a short term. The most memorable thing I learned from my mentor and the thing I’m still working to practice every day while coding is that a function shouldn’t exceed 10 lines. It may sound provocative, but in essence, I understood it as a rule that a function needs to be designed to carry out only one task.

If you try to write it in less than 10 lines, the function continues to break down into smaller features and it gives you more time to think about designing relationships between each object. Furthermore, chaining functions without side effects has the advantage that code is easily read and modified. This especially shines when used with Swift’s methods such as map, flatMap, compactMap, filter, etc.

In Promises, functions can be chained with then, always, validate, etc.

Example:

extension CNContact {

var mainPhoneNumber: String? {

return phoneNumbers.map { $0.value.stringValue }

.filter(prefixValidater)

.map(replaceKoreanCountryCode)

.map(removeNonNumerics)

.filter { $0.isPhoneNumber && $0.count == 11}

.first

}

private func prefixValidater(_ target: String) -> Bool { ... }

private func replaceKoreanCountryCode(_ digits: String) -> String { ... }

private func removeNonNumerics(_ digits: String) -> String { ... }

}

Conveying meaningful error messages to users

After several years of developing mobile apps, I had a thirst for how to handle errors well.

The step that happens most frequently in a mobile app is user interaction 👉 a series of tasks to process the request

👉 displaying the results on the screen. As a series of tasks are being processed, various errors may occur. The data may be corrupted, the network may be unstable, the server may be down, or you may have no permission to access it. In this case, rather than simply showing a meaningless message that says, “Request Failure,” letting the user know the cause of failure is much better in terms of user experience. You can make use of localizedDescription of NSError, or Error or LocalizedError protocol on Swift. In Promises, you can uniformly receive errors that occurred during several consecutive asynchronous operations in the final stage, and there’s even an opportunity to recover them.

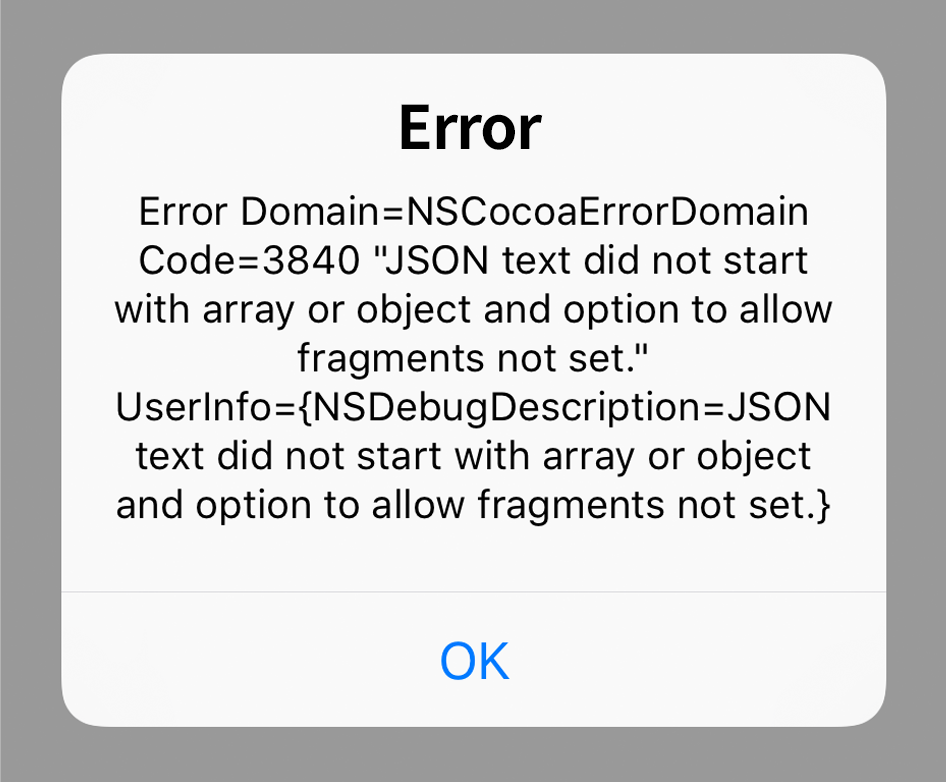

Are you going to show an error message like this?

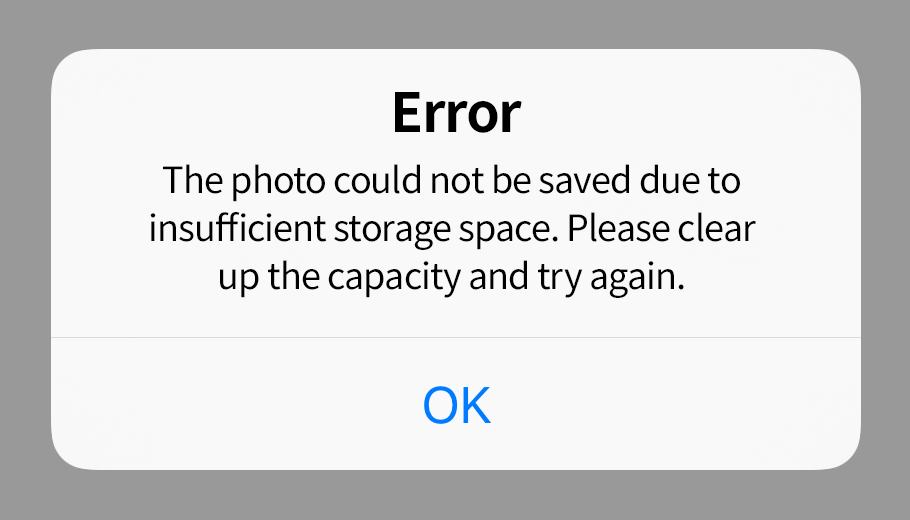

Or are you going to show a message that is actually helpful to the user?

Minimizing dependencies

There’s a subtle repulsion to using some ~Kits that go around the standard library. I’m the person who goes around with no protection film on my iPhone, so I’m very reluctant to add a 10-size library just for a 1-size feature, and other things on CocoaPods just to use them in one or two projects.

I’m using auto layouts without a separate library, and I was once interested in Rx so I used to study it, but eventually neglected it because it seemed like over-customizing. As they say, the end of customizing is original. Because I prefer the original, I think Promises goes ahead in performance because it wraps GCDs lighter than other similar libraries, and learning it costs less as well.

Adopting Promises to Your Project

Because you’re introducing Promises, you don’t have to redo the whole project. It’s good to apply it step by step in practical work. Usually, there is a class in charge of each characteristic of a task. (e.g. login manager, image downloader class, etc.) It’s enough to apply it only in one or two of these classes first. If you use the wrap, you don’t have to change the existing codes and create an asynchronous function in a Promise style with only a few lines of code.

A function that originally received a completion handler as a parameter:

func data(from url: URL, completion: @escaping (Data?, Error?) -> Void)

An asynchronous function that was modified to return a Promise object:

func data(from url: URL) -> Promise<Data>

Then create a Promise object and return it within the function, and carry out additional tasks with the resulting values that are/will be fulfilled.

let url = ...

data(from: url).then { data in

//additional task using data

}.catch { error in

//error handling

}

Additional uses are clearly and concisely explained in the document.

Use Cases

I’ve organized some use cases and precautions that I’ve learned through trial and error while using Promises.

Partial Application 기법

I’d like to introduce how to apply the partial application technique to increase the readability of the Promises pipeline and function reusability. There’s a high probability that you have tried using it if you were using higher-order functions such as map, forEach, etc.

The task of acquiring the access token after logging in to the API server is an indispensable task

in log-in based services. The virtual login steps are as follows. Sign up 👉 Log in 👉 acquire an access token. But if you’re already registered, you’ll fail to sign up. There is a chance to recover from the failure in Promises by using recover. So if the cause of failure to sign in is a duplicate user, attempt to log in.

Promises Code:

typealias MyAccessToken = String

func retrieveAccessToken(with naverToken: String) -> Promise<MyAccessToken> {

return requestSignUp(with: naverToken)

.then(signIn(with: naverToken))

.recover(onError(with: naverToken))

}

//Async Server API calls

func requestSignUp(with naverToken: String) -> Promise<SignUpResponse> { ... }

func requestSignIn(with naverToken: String) -> Promise<MyAccessToken> { ... }

//partially applied functions

func signIn(with naverToken: String) -> (SignUpResponse) -> Promise<MyAccessToken> {

return { _ in requestSignIn(with: naverToken) }

}

func onError(with naverToken:String) -> (Error) -> Promise<MyAccessToken> {

return { error in

switch error {

case SignUpError.duplicateUser:

return requestSignIn(with: naverToken)

default:

return Promise(error)

}

}

}

signIn(with:) and onError(with:) are partially applied functions that are designed to receive the SignUpResponse and Error parameters later. When chaining this way, I did not use the closure right away and used a partial application to reuse the existing API-related functions and at the same time, made the asynchronous task pipeline much easier to read.

The task that is impossible with simple chaining is await.

Await is useful when it needs to be used with combined results from several asynchronous tasks.

For example, suppose there’s a task that requires the UIImage and its major UIColor to be extracted and drawn on the screen using the URL for the thumbnail image. In short, convert the URL to UIImage 👉 extract UIColor from the UIImage 👉 create a thumbnail using UIImage and UIColor on the screen. This task was difficult to implement with then chaining alone, and it was resolved with await. This method can be used when you want to use an asynchronous task like a synchronous code.

Promises Code:

typealias ThumbnailData = (image: UIImage, color: UIColor)

func thumbnailData(from url: URL) -> Promise<ThumbnailData> {

return Promise<ThumbnailData>(on: queue) { //queue는 백그라운드 DispatchQueue

let image = try await(image(from: url))

let color = try await(dominantColor(from: image))

return (image: image, color: color)

}

}

//Async functions

func image(from url: URL) -> Promise<UIImage> { ... }

func dominantColor(from image: UIImage) -> Promise<UIColor> { ... }

Applied Code:

let cell: MyTableViewCell = ...

let myDatum = data[indexPath.row]

let url: URL = myDatum.imageURL

thumbnailData(from: url).then { result in

cell.imageView.image = result.image

cell.dominantColorView.backgroundColor = result.color

}

Additionally, something important to note before using Promises,

Wrap Up

I recommend you to try this if you’ve had any regrets with asynchronous programming done in a completion handler method or if you’ve ever thought that Rx is way too vast for you while working in iOS development. I think Google/Promises is a good framework that makes asynchronous code flexible with minimal code modifications, increases readability, and is able to try many things with a small learning cost.

Tags: swift, promises, async programming, error handling